One of the most important aspects of writing maintainable code is being able to notice the repeating themes in that code and optimize them. This is an area where knowledge of design patterns can prove invaluable.

I take a look at a number of popular JavaScript design patterns and explore why certain patterns may be suitable for your projects.

Why is it important to understand patterns and be familiar with them?

So, why is it important to understand patterns and be familiar with them? Design patterns have three main benefits:

- Patterns are proven solutions: They provide solid approaches to solving issues in software development using proven techniques that reflect the experience and insights the developers that helped define them bring to the pattern.

- Patterns can be easily reused: A pattern usually reflects an out of the box solution that can be adapted to suit our own needs.

- Patterns can be expressive: When we look at a pattern there’s generally a set structure and vocabulary to the solution presented that can help express rather large solutions quite elegantly.

Categories Of Design Pattern

Design patterns can be broken down into a number of different categories. In this section we’ll review three of these categories:

Creation Design Patterns

The basic approach to object creation might otherwise lead to added complexity in a project whilst these patterns aim to solve this problem by controlling the creation process.

Some of the patterns that fall under this category are: Constructor, Factory, Prototype, Singleton.

Structural Design Patterns

Typically identify simple ways to realize relationships between different objects.

Patterns that fall under this category include: Decorator, Facade, Flyweight.

Behavioral Design Patterns

Behavioral patterns focus on improving the communication between disparate objects in a system.

Some behavioral patterns include: Mediator, Observer.

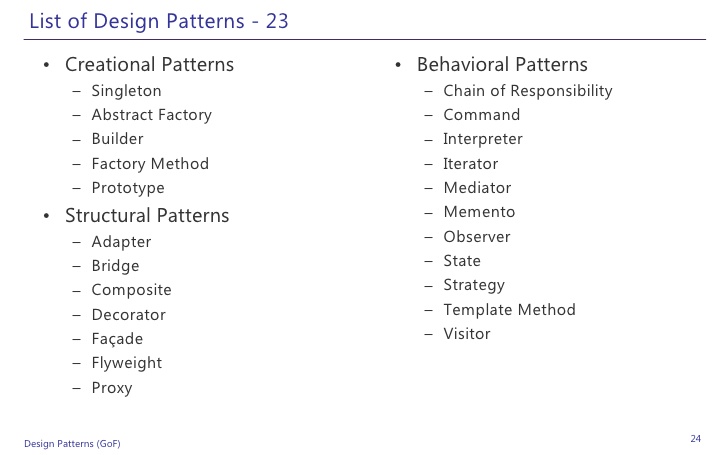

Table of 23 Design Patterns mentioned by the GoF

I personally found the following table a very useful reminder of what a number of patterns has to offer - it covers the 23 Design Patterns mentioned by the GoF:

Creation Design Patterns in depth

Developers commonly wonder whether there is an ideal pattern or set of patterns they should be using in their workflow. There isn’t a true single answer to this question; each script and web application we work on is likely to have its own individual needs and we need to think about where we feel a pattern can offer real value to an implementation.

The Constructor Pattern

In classical object-oriented programming languages, a constructor is a special method used to initialize a newly created object once memory has been allocated for it.

In JavaScript, as almost everything is an object, we’re most often interested in object constructors.

Object Creation

// Each of the following options will create a new empty object:

const newObject = {};

// or

const newObject = Object.create( Object.prototype );

// or

const newObject = new Object();

Where the Object constructor in the final example creates an object wrapper for a specific value, or where no value is passed, it will create an empty object and return it.

Basic Constructors

By simply prefixing a call to a constructor function with the keyword new, we can tell JavaScript we would like the function to behave like a constructor and instantiate a new object with the members defined by that function.

Inside a constructor, the keyword this references the new object that’s being created:

function Car( model, year, miles ) {

Object.assign(this, { model, year, miles });

this.toString = function () {

return `${this.model} has done ${this.miles} miles`;

};

}

// Usage:

const civic = new Car( "Honda Civic", 2009, 20000 );

const mondeo = new Car( "Ford Mondeo", 2010, 5000 );

console.log( civic.toString() );

console.log( mondeo.toString() );

Constructors With Prototypes

Functions, like almost all objects in JavaScript, contain a prototype object. When we call a JavaScript constructor to create an object, all the properties of the constructor’s prototype are then made available to the new object:

function Car( model, year, miles ) {

Object.assign(this, { model, year, miles });

}

// Note here that we are using Object.prototype.newMethod rather than

// Object.prototype so as to avoid redefining the prototype object

Car.prototype.toString = () => `${this.model} has done ${this.miles} miles`;

// Usage:

const civic = new Car( "Honda Civic", 2009, 20000 );

const mondeo = new Car( "Ford Mondeo", 2010, 5000 );

console.log( civic.toString() );

console.log( mondeo.toString() );

Constructors with ES6 class

const Car = class {

constructor(props) {

Object.assign(this, props);

}

toString() {

return `${this.model} has done ${this.miles} miles`;

}

}

// Usage:

const civic = new Car( {model: "Honda Civic", year: 2009, miles: 20000} );

const mondeo = new Car( {model: "Honda Civic", year: 2009, miles: 20000} );

console.log( civic.toString() );

console.log( mondeo.toString() );

Constructors with ES6 class for Node.js

// in the end/or better on the beginning share you constructor

module.exports = Car;

Constructors in Angular1.x

// Task.factory.js

const app = angular.module('taskManager');

app.factory('Task', () => {

const Task = class {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

this.completed = false;

}

complete() {

this.complete = true;

console.log(`compete task: ${this.name}`);

}

save() {

console.log(`save task: ${this.name}`);

}

}

return Task;

})

The Module Pattern

Modules are an integral piece of any robust application’s architecture and typically help in keeping the units of code for a project both cleanly separated and organized.

In JavaScript, there are several options for implementing modules. These include:

- The Module pattern

- Object literal notation

- AMD modules

- CommonJS modules

- ES6 modules

The Revealing Module Pattern

We would simply define all of our functions and variables in the private scope and return an anonymous object with pointers to the private functionality we wished to reveal as public:

var myRevealingModule = (function () {

var privateVar = "Ben Cherry",

publicVar = "Hey there!";

function privateFunction() {

console.log( "Name:" + privateVar );

}

function publicSetName( strName ) {

privateVar = strName;

}

function publicGetName() {

privateFunction();

}

// Reveal public pointers to

// private functions and properties

return {

setName: publicSetName,

greeting: publicVar,

getName: publicGetName

};

})();

myRevealingModule.setName( "Paul Kinlan" );

The Module Pattern for Node.js

// just export what you need

module.exports = myRevealingModule();

// Usage:

var myModule = require('./myRevealingModule');

// module.setName...

The Module Pattern for Angular1.x

// taskRepo.factory.js

const = app.module(taskManager);

app.factory(taskRepo);

function taskRepo($http) {

const db = {};

const get = (id) => {

log(`Getting task ${id}`);

}

const save = (task) => {

log(`Save ${task.nae} to the db`);

}

return { get, save };

}

taskRepo.$inject = ['$http'];

The Singleton Pattern

In JavaScript, Singletons serve as a shared resource namespace which isolate implementation code from the global namespace so as to provide a single point of access for functions:

class Singleton {

static instance;

constructor(){

if(instance){

return instance;

}

this.state = "duke";

this.instance = this;

}

}

// usage

const first = new Singleton();

const second = new Singleton();

console.log(first === second); // true

The Singleton Pattern for Node.js

From Node.js docs information about caching modules:

Modules are cached after the first time they are loaded. This means (among other things) that every call to require('foo') will get exactly the same object returned, if it would resolve to the same file.

If you want to have a module execute code multiple times, then export a function, and call that function.

// repo.js

// just return a function call

// for singleton

module.exports = repo();

// import a singleton

const require = repo();

The Singleton Pattern for Angular1.x

By default all service all singleton, because they are providers, more info here.

The Factory Pattern

Factory provide a generic interface for creating objects, where we can specify the type of factory object we wish to be created.

Imagine that we have a UI factory where we are asked to create a type of UI component. Rather than creating this component directly using the new operator or via another creation constructor, we ask a Factory object for a new component instead. We inform the Factory what type of object is required (e.g Button, Panel) and it instantiates this, returning it to us for use:

// Types.js - Constructors used behind the scenes

// A constructor for defining new cars

function Car( options ) {

// some defaults

this.doors = options.doors || 4;

this.state = options.state || "brand new";

this.color = options.color || "silver";

}

// A constructor for defining new trucks

function Truck( options){

this.state = options.state || "used";

this.wheelSize = options.wheelSize || "large";

this.color = options.color || "blue";

}

// FactoryExample.js

// Define a skeleton vehicle factory

function VehicleFactory() {}

// Define the prototypes and utilities for this factory

// Our default vehicleClass is Car

VehicleFactory.prototype.vehicleClass = Car;

// Our Factory method for creating new Vehicle instances

VehicleFactory.prototype.createVehicle = function ( options ) {

switch(options.vehicleType){

case "car":

this.vehicleClass = Car;

break;

case "truck":

this.vehicleClass = Truck;

break;

//defaults to VehicleFactory.prototype.vehicleClass (Car)

}

return new this.vehicleClass( options );

};

// Create an instance of our factory that makes cars

var carFactory = new VehicleFactory();

var car = carFactory.createVehicle( {

vehicleType: "car",

color: "yellow",

doors: 6 } );

// Test to confirm our car was created using the vehicleClass/prototype Car

// Outputs: true

console.log( car instanceof Car );

// Outputs: Car object of color "yellow", doors: 6 in a "brand new" state

console.log( car );

Abstract Factories

It is also useful to be aware of the Abstract Factory pattern, which aims to encapsulate a group of individual factories with a common goal.

It separates the details of implementation of a set of objects from their general usage:

var abstractVehicleFactory = (function () {

// Storage for our vehicle types

var types = {};

return {

getVehicle: function ( type, customizations ) {

var Vehicle = types[type];

return (Vehicle ? new Vehicle(customizations) : null);

},

registerVehicle: function ( type, Vehicle ) {

var proto = Vehicle.prototype;

// only register classes that fulfill the vehicle contract

if ( proto.drive && proto.breakDown ) {

types[type] = Vehicle;

}

return abstractVehicleFactory;

}

};

})();

// Usage:

abstractVehicleFactory.registerVehicle( "car", Car );

abstractVehicleFactory.registerVehicle( "truck", Truck );

// Instantiate a new car based on the abstract vehicle type

var car = abstractVehicleFactory.getVehicle( "car", {

color: "lime green",

state: "like new" } );

// Instantiate a new truck in a similar manner

var truck = abstractVehicleFactory.getVehicle( "truck", {

wheelSize: "medium",

color: "neon yellow" } );

Structural Design Patterns in depth

Structural design patterns are ones that focus on easing the relationship between different components of an application. They help to provide stability by ensuring that if one part of the app changes, the entire thing doesn’t need to as well.

Mixins

Mixins allow objects to borrow (or inherit) functionality from them with a minimal amount of complexity.

Imagine that we define a Mixin containing utility functions in a standard object literal as follows:

var myMixins = {

moveUp: function(){

console.log( "move up" );

},

moveDown: function(){

console.log( "move down" );

},

stop: function(){

console.log( "stop! in the name of love!" );

}

};

We can then easily extend the prototype of existing constructor functions to include this behavior using a helper such as the Underscore.js _.extend() method:

// A skeleton carAnimator constructor

function CarAnimator(){

this.moveLeft = function(){

console.log( "move left" );

};

}

// A skeleton personAnimator constructor

function PersonAnimator(){

this.moveRandomly = function(){ /*..*/ };

}

// Extend both constructors with our Mixin

_.extend( CarAnimator.prototype, myMixins );

_.extend( PersonAnimator.prototype, myMixins );

// Create a new instance of carAnimator

var myAnimator = new CarAnimator();

myAnimator.moveLeft();

myAnimator.moveDown();

myAnimator.stop();

// Outputs:

// move left

// move down

// stop! in the name of love!

Mixins with ES6

Object.assign( CarAnimator.prototype, myMixins );

Object.assign( PersonAnimator.prototype, myMixins );

The Decorator Pattern

The Decorator pattern isn’t heavily tied to how objects are created but instead focuses on the problem of extending their functionality.

Adding new attributes to objects in JavaScript is a very straight-forward process so with this in mind, a very simplistic decorator may be implemented as follows:

// The constructor to decorate

function MacBook() {

this.cost = function () { return 997; };

this.screenSize = function () { return 11.6; };

}

// Decorator 1

function memory( macbook ) {

var v = macbook.cost();

macbook.cost = function() {

return v + 75;

};

}

// Decorator 2

function engraving( macbook ){

var v = macbook.cost();

macbook.cost = function(){

return v + 200;

};

}

// Decorator 3

function insurance( macbook ){

var v = macbook.cost();

macbook.cost = function(){

return v + 250;

};

}

var mb = new MacBook();

memory( mb );

engraving( mb );

insurance( mb );

// Outputs: 1522

console.log( mb.cost() );

// Outputs: 11.6

console.log( mb.screenSize() );

The Decorator Pattern in Angular1.x

More information about decorator method in off documentation or here

angular.module( "Demo", [] );

angular.module( "Demo" ).run(

function runBlock( greeting ) {

console.log( greeting( "Joanna" ) );

}

);

angular.module( "Demo" ).factory(

"greeting",

function greetingFactory() {

return( greeting );

// I return a greeting for the given name.

function greeting( name ) {

return( "Hello " + name + "." );

}

}

);

angular.module( "Demo" ).decorator(

"greeting",

function greetingDecorator( $delegate ) {

// Return the decorated service.

return( decoratedGreeting );

// I append a new message to the existing greeting.

function decoratedGreeting( name ) {

return( $delegate( name ) + " How are you doing?" );

}

}

);

Sub-classing

Sub-classing is a term that refers to inheriting properties for a new object from a base or superclass object. In traditional object-oriented programming, a class B is able to extend another class A. Here we consider A a superclass and B a subclass of A. As such, all instances of B inherit the methods from A. B is however still able to define its own methods, including those that override methods originally defined by A.

We first need a base object:

var Person = function( firstName, lastName ){

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.gender = "male";

};

Next, we’ll want to specify a new class (object) that’s a subclass of the existing Person object:

// a new instance of Person can then easily be created as follows:

var clark = new Person( "Clark", "Kent" );

// Define a subclass constructor for for "Superhero":

var Superhero = function( firstName, lastName, powers ){

// Invoke the superclass constructor on the new object

// then use .call() to invoke the constructor as a method of

// the object to be initialized.

Person.apply( this, arguments );

// Finally, store their powers, a new array of traits not found in a normal "Person"

this.powers = powers;

};

Superhero.prototype = Object.create( Person.prototype );

var superman = new Superhero( "Clark", "Kent", ["flight","heat-vision"] );

Sub-classing with ES6

class Person {

constructor ( firstName, lastName, gender = "male" ){

Object.assign(this, { firstName, lastName, gender });

};

}

class Superhero extends Person {

constructor ( firstName, lastName, gender, powers ){

super(firstName, lastName, gender);

this.powers = powers;

};

}

// usage

const superman = new Superhero( "Clark", "Kent", "female", ["flight","heat-vision"] );

The Facade Pattern

This pattern provides a convenient higher-level interface to a larger body of code, hiding its true underlying complexity.

Whenever we use jQuery’s $(el).css() or $(el).animate() methods, we’re actually using a Facade - the simpler public interface that avoids us having to manually call the many internal methods in jQuery core required to get some behavior working.

In a similar manner, we’re all familiar with jQuery’s $(document).ready(..). Internally, this is actually being powered by a method called bindReady(), which is doing this:

bindReady: function() {

...

if ( document.addEventListener ) {

// Use the handy event callback

document.addEventListener( "DOMContentLoaded", DOMContentLoaded, false );

// A fallback to window.onload, that will always work

window.addEventListener( "load", jQuery.ready, false );

// If IE event model is used

} else if ( document.attachEvent ) {

document.attachEvent( "onreadystatechange", DOMContentLoaded );

// A fallback to window.onload, that will always work

window.attachEvent( "onload", jQuery.ready );

...

Flyweight

The Flyweight pattern is a classical structural solution for optimizing code that is repetitive, slow and inefficiently shares data. It aims to minimize the use of memory in an application by sharing as much data as possible with related objects

There are two ways in which the Flyweight pattern can be applied. The first is at the data-layer, where we deal with the concept of sharing data between large quantities of similar objects stored in memory.

The second is at the DOM-layer where the Flyweight can be used as a central event-manager to avoid attaching event handlers to every child element in a parent container we wish to have some similar behavior.

Behavior Design Patterns in depth

The observer

The Observer is a design pattern where an object (known as a subject) maintains a list of objects depending on it (observers), automatically notifying them of any changes to state.

We can now expand on what we’ve learned to implement the Observer pattern with the following components:

- Subject: maintains a list of observers, facilitates adding or removing observers

- Observer: provides a update interface for objects that need to be notified of a Subject’s changes of state

- ConcreteSubject: broadcasts notifications to observers on changes of state, stores the state of ConcreteObservers

- ConcreteObserver: stores a reference to the ConcreteSubject, implements an update interface for the Observer to ensure state is consistent with the Subject’s

First, let’s model the list of dependent Observers a subject may have:

function ObserverList(){

this.observerList = [];

}

ObserverList.prototype.add = function( obj ){

return this.observerList.push( obj );

};

ObserverList.prototype.count = function(){

return this.observerList.length;

};

ObserverList.prototype.get = function( index ){

if( index > -1 && index < this.observerList.length ){

return this.observerList[ index ];

}

};

ObserverList.prototype.indexOf = function( obj, startIndex ){

var i = startIndex;

while( i < this.observerList.length ){

if( this.observerList[i] === obj ){

return i;

}

i++;

}

return -1;

};

ObserverList.prototype.removeAt = function( index ){

this.observerList.splice( index, 1 );

};

The Subject and the ability to add, remove or notify observers on the observer list:

function Subject(){

this.observers = new ObserverList();

}

Subject.prototype.addObserver = function( observer ){

this.observers.add( observer );

};

Subject.prototype.removeObserver = function( observer ){

this.observers.removeAt( this.observers.indexOf( observer, 0 ) );

};

Subject.prototype.notify = function( context ){

var observerCount = this.observers.count();

for(var i=0; i < observerCount; i++){

this.observers.get(i).update( context );

}

};

Full example here

Differences Between The Observer And Publish/Subscribe Pattern

Whilst the Observer pattern is useful to be aware of, quite often in the JavaScript world, we’ll find it commonly implemented using a variation known as the Publish/Subscribe pattern.

The Publish/Subscribe pattern however uses a topic/event channel which sits between the objects wishing to receive notifications (subscribers) and the object firing the event (the publisher).

This event system allows code to define application specific events which can pass custom arguments containing values needed by the subscriber. The idea here is to avoid dependencies between the subscriber and publisher.

Here is an example of how one might use the Publish/Subscribe if provided with a functional implementation powering publish(),subscribe() and unsubscribe() behind the scenes:

var eventBus = (function(){

var topics = Object.create({});

return {

subscribe: function(topic, listener) {

// Create the topic's object if not yet created

if(!topics[topic]) topics[topic] = [];

// Add the listener to queue

var index = topics[topic].push(listener) -1;

// Provide handle back for removal of topic

return {

unsubscribe: function() {

delete topics[topic][index];

}

};

},

publish: function(topic, info) {

// If the topic doesn't exist, or there's no listeners in queue, just leave

if(!topics[topic]) return;

// Cycle through topics queue, fire!

topics[topic].forEach(function(item) {

item(info != undefined ? info : {});

});

}

};

})();

Subscribe in order to be notified for events:

var subscription = events.subscribe('/page/load', function(obj) {

// Do something now that the event has occurred

});

// ...sometime later where I no longer want subscription...

subscription.unsubscribe();

Publishing:

events.publish('/page/load', {

url: '/some/url/path' // any arguments

});